|

|

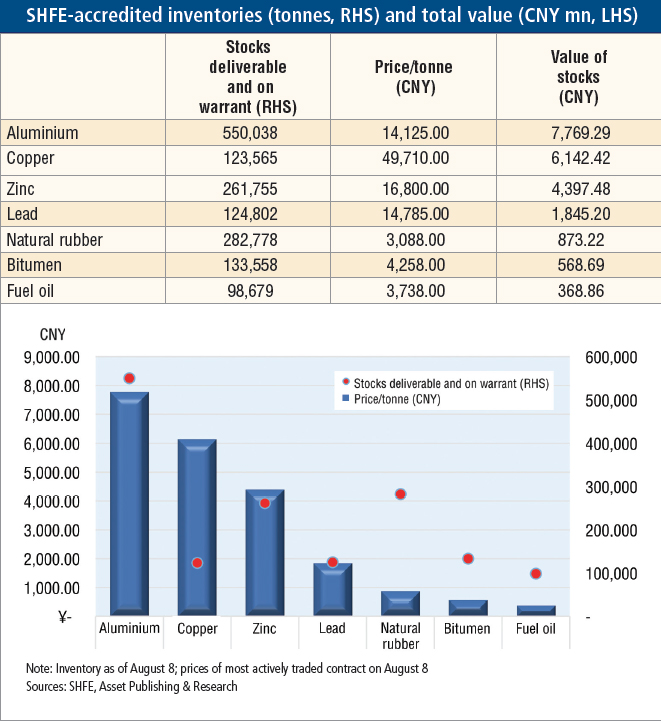

| SHFE-accredited inventories (tonnes, RHS) and total value (CNY mn, LHS) (Click to enlarge) |

In November 1963, on the weekend of John F Kennedy’s assassination, another piece of news went largely unnoticed. More than 50 investors had fallen prey to an almost comical fraud, serving as a case study even today. At the centre of it stood Anthony De Angelis, son of Italian immigrants and the Bronx in New York City. For the past eight years, he had built a trading house dealing with soft commodities including soybean oil. Quickly, he had realized that his business, Allied Crude Vegetable Oil Refining Co, makes for a great candidate of commodity-backed financing – which happened to be a growing field for financial institutions at the time.

Almost as quickly, he also figured out how to cheat the system. Lending his company some of the largest sums was American Express, keen to grow its business of providing working capital loans backed by inventories of commodities as collateral. As a measure of precaution, the company sent inspectors to the port and warehouses to check whether De Angelis really did own the vegetable oil he reported. But De Angelis was prepared for their arrival each and every time, filling tanks with just enough oil to cover the water beneath and linking tanks with each other so that inspectors would be fooled as they proceeded from tank to tank.

His crooked methods worked so well that De Angelis was able to secure loans from 51 financial institutions that believed he possessed quantities of vegetable oil worth US$150 million. No more than the equivalent of US$6 million was eventually recovered when the scam was exposed. Two large brokerage houses were forced to file for bankruptcy in November 1963 as a result of Allied Crude’s failure. Creditors lost millions and De Angelis, known to many as the Salad Oil King, spent the next seven years in jail.

The genesis

Fast forward 50 years and an equally elaborate fraud is sending shockwaves through the banking industry, but this time in China and with some much more bizarre consequences.

At the centre of the Qingdao port scandal, which first surfaced on May 30 this year as a result of police investigations, is Chen Jihong, a Singapore national and founder of metals trading house Decheng Mining. Chen is suspected to have used fake warehouse receipts as collateral for financing, pledging the same stock of metal with multiple lenders for loans. He also sold these receipts, or warrants, to unsuspecting corporates that used them as collateral for loans themselves. Reportedly, a total of 18 global and local banks have lent the company and its clients nearly 15 billion yuan (US$2.4 billion), of which some or all may be in jeopardy.

How much metal can be salvaged from the warehouses at Qingdao port in Shandong province is still not yet clear. Initially, Chinese port authorities estimated the discrepancy between what the company actually owned and what it claimed to have to be around 100,000 tonnes of aluminium and 3,000 tonnes of copper.

Yet, CITIC Resources in early July sued Hong Kong listed Qingdao Port Group for over 220,000 tonnes of aluminium and 5,000 tonnes of copper that are missing. It seeks compensation of more than US$100 million if the metals cannot be delivered.

|

|

| Ng: Inventory financing requires a more hands-on approach |

While the largest exposure to Decheng Mining, its affiliated companies and clients is on the part of Chinese banks, foreign banks are exposed to the case directly and indirectly. On August 6, Standard Chartered announced a US$175 million one-off provision as a result of the Qingdao port probe. According to Andrew Halford, group finance director, US$62 million of that figure has already been booked as loan impairment.

Banks that have taken legal action against Chen Jihong or one of his companies include Standard Chartered, HSBC and ABN AMRO. Other institutions with exposure to the case include Citi and Standard Bank. Mercuria Energy Trading, too, has been implicated as it had reportedly obtained financing from Citi on the back of metals stored in Qingdao – on loan from Decheng Mining.

Among Chinese banks, China Export and Import Bank and ICBC are believed to have the largest exposure to the case.

Immediate fallout

The struggle over ownership and compensation will be carried out in Chinese and international arbitration courts over the coming months and years, but there is more at stake than the billions of US dollars in potential losses.

The most immediate fallout of the probe has been a drop in copper imports to China, as banks take a more cautious stance on financing stocks of the metal. Imports of copper fell 7.9% month-on-month in June and a further 4% in July, customs data show. Compared to last year, they are down 15.6%.

An indicator even more illuminating is that of bonded copper stocks in China, which dropped nearly 20% in June vis-à-vis May, according to Reuters. While macroeconomic factors and a summer lull in many manufacturing industries played a role, the hefty drop shines light on a different group of commodity importers. Speculators seeking to exploit currency appreciation and interest rate arbitrage for years have circumvented capital controls with the use of complex commodity financing transactions.

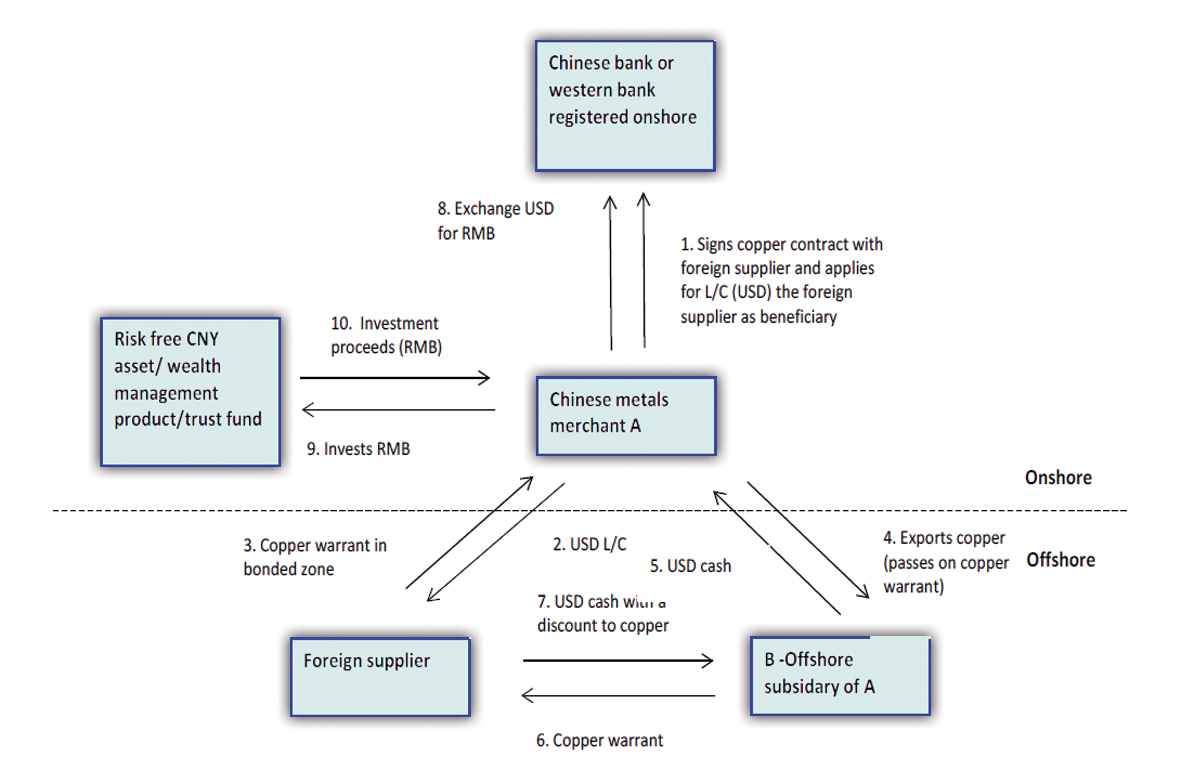

In such a transaction, an offshore trading house sells copper (or another commodity that is compact and valuable) to onshore parties (See diagram). It is paid by the onshore party’s bank in form of a letter of credit (L/C), denominated in US dollar, which carries much lower interest rates than financing in yuan. The onshore party will then re-export the copper by transferring the warrant, or receipt, of the warehouse to an offshore party (which is owned by the initial exporter). That party will pay the onshore exporter in CNH directly or in US dollar, in which case it would be exchanged into local currency.

The onshore party now can invest these proceeds in China, including in higher yielding wealth management products (WMP). At the end of the L/C terms, typically 180 days or longer, the onshore party will repay the US dollar letter of credit, which carried a much lower interest rate than the WMPs and – if the renminbi appreciated – will have become cheaper over time. Various variations of this scheme are possible.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs estimate that commodities-backed lending has resulted in inflows of US$110 billion of foreign currency-denominated short term debt over the past four years – representing one-fourth of FCY loans. How much of that has been purely for the purpose of capital account circumvention is difficult to gauge. Even more difficult to know is how much of this lending is backed by fake warrants or whether Decheng Mining is an isolated case only.

Certainly, the 20% drop in inventory is a strong indication that import letters of credit are not rolled over by banks as long as they are not in a position to find answers to these questions. Until then, speculators need to sell metal stocks to settle outstanding loans.

|

|

| Cripps: If your inventory is claimed by another bank, you have a problem |

Crossing the grey line

Capital account circumvention is not the only purpose of commodity-based financing, of course. Businesses with real needs dominate flows. At the same time, though, another practice involving commodity stocks that crosses into grey line territory exists.

China is infamous for high onshore cost of funding, particularly in sectors such as real estate. At the same time, the economy has been riddled with oversupply of certain commodities including aluminium. A very lucrative business has mushroomed as a result of the plights these two separate industries face.

“If you were an aluminium producer in China with a whole lot of stock on hand, you find you can earn quite a good commission by making that stock available to act as a security for other borrowers,” explains Michael Cripps, a Shanghai-based partner at law firm Clyde & Co. “There is a lot of aluminium floating through the system and with prices depressed until fairly recently, a lot of it had been hanging around in warehouses.”

Through a broker, which may or may not be a financial institution, real estate developers and other businesses at the speculative end of the market could take out loans based on commodity inventories of producers that had no use for them anyway. The vast majority of these arrangements are legitimate, Cripps adds, backed by just one warehouse receipt banks require.

Yet, the step to collude with warehouse owners and issue multiple receipts on these inventories has likely been a small one for a few commodity owners such as Dezheng Mining chasing commissions. In that case, risk modelling of the banks becomes irrelevant.

“No matter how good the credit worthiness of your borrower, if you suddenly have 50 borrowers backed by the same inventory and one of them goes bust – and that inventory is claimed by another bank as a result – you have a problem,” Cripps quips.

Sizing the business

Putting a number to commodity-backed financing is difficult in the absence of official figures. Looking at the inventory of warehouses accredited by the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE), more than 1.57 million tonnes of aluminium, copper, zinc and other commodities are currently stored, either deliverable or on warrant. If 20% of that inventory is tied up in financing arrangements (at 100% face value), loans worth 4.4 billion renminbi are backed by these resources across the SHFE warehouses alone.

The SHFE has accredited less than 60 warehouses across the country, of which only around 25 are allowed to store aluminium and copper. Nationwide, hundreds of other warehouses exist, storing many other types of commodities that are used as collateral in financing arrangements as well, including iron ore, steel products, soybeans, gold and even cotton. SHFE warehouse figures therefore only provide a glimpse of the total value of commodity-backed financing in China – for both real and speculative uses.

Some analysts at Chinese securities houses have estimated at least one-third of total copper stocks in China (placed at 850,000 tonnes by Deutsche Bank) are only used for the purpose of financing deals, which would amount to about 14 billion renminbi in loans backed by the reddish-brown metal (at 3M SHFE futures prices).

Juxtaposed with China’s overall debt levels and credit supply, though, these figures hardly cause alarm. Weighing more heavily, loss of confidence in the financial supply chain of commodity-backed lending may have a negative impact on more traditional sources of trade finance as well. Initial fears that trade finance will freeze up more broadly, though, seem not to have crystallized.

Jayant Parande, senior vice-president and group treasurer at Singapore’s Olam International, says the group “has not come across any perceptible drop in letter of credit financing by banks for our customers in China. One of the reasons could be the fact that we are focused only on agricultural commodities as an asset class.”

Olam imports goods worth US$250 million-US$500 million per annum into China. It does not use commodity-backed financing arrangements itself.

The China treasurer of a US trading house also gives testament that trade finance liquidity has not dried up: “We import phosphate and potash from our parent company. We have not noticed any squeeze in trade finance, but we did discuss the matter with our bank,” she points out. “They do not have any exposure to the Qingdao issue and I believe this is an isolated case.”

Banks with exposure to the scandal, too, stress their unbridled commitment to the market. A spokesperson for Standard Chartered says that only a small number of clients have been impacted in the Shandong region, including the Qingdao port, and that the bank is reviewing its exposures to commodity financing.

“We remain committed to this business and to our clients in this sector,” she notes. “We are not pulling back from providing commodity (metals) financing nor are we pulling back from China which is a key market for the bank.”

Jacqueline Chang, regional head of commodities for Asia at ABN AMRO, replies in a similar vein: “We intend to continue as a key player in the commodity trade finance space and have every confidence in our specialized sector experience and capabilities to continue supporting our metals commodities clients in China and across the region.”

Lynn Ng, head, commodities group for South Asia, at ING Bank, notes that the bank has had more inquiries from existing clients to provide financing on their metals. While a “tempting conclusion”, she refrains from attributing the rise in demand to other banks pulling back from the business in China. ING had no exposure to the companies involved in the Qingdao case, she also adds.

“Inventory financing does involve a bit more risk and requires a more hands-on approach,” she suggests. “There is some overcapacity in some industries in China, but we focus on finding those local companies with sustainable success factors. For example, if you have a steel mill that produces competitive products demanded by end users, then you have a sustainable business model. My job is to find those steel mills.”

ICBC goes too far

Behind the scenes, though, the issue of fake warehouse receipts at Qingdao port has long reached the top echelons of both banks and politics. “When the news came out, we got a lot of e-mails from the very top, asking what is going on,” says one senior banker who requested anonymity. “We also got calls from other bankers asking what we have heard.”

ICBC, the world’s largest bank by market capitalization, did its fair share to add to the woes in mid-July. Shaking trade finance principles at their very core, the bank launched a bizarre injunction against itself in a Chinese court, only so it would not have to honour an L/C it had issued – a process one source calls “ludicrous”.

Apparently, ICBC had issued an L/C as part of a back-to-back trade finance transaction on behalf of a global bank, which arranged the transaction based on relations with the client offshore. The name of the client has not been confirmed. Instead of honouring the L/C, ICBC tried to avoid payment after news of the scandal broke, which would have left the global counterparty bank stuck with the obligation for payment.

Asked about the case by an analyst in a conference call, DBS’ chief executive officer Piyush Gutpa summarized the significance ICBC’s self-injunction carries: “Once a bank has accepted documents, no bank ever reneges.”

ICBC was well beyond having accepted the necessary L/C documents. Two sources have confirmed to The Asset that ICBC has indeed made payment after political pressure caused the bank to relent.

|

|

| How copper financing works (Click to enlarge) |

LME patiently waits

Watching the scandal unfold is the London Metal Exchange and its new Hong Kong owner, HKEx (Hong Kong Stock Exchange and Clearing).

A centralized registry of warehouse receipts – a key feature of the LME – could have easily prevented the Qingdao case. In China, only the Shanghai Futures Exchange has such a system (aside from a few very minor exchanges elsewhere). Receipts from the vast amount of warehouses in China are not issued and tracked electronically and therefore more easily duplicated. The LME has not been allowed to accredit warehouses in China.

The Qingdao port scandal, thus, calls for one of two things to happen: either a regulation that requires all warrants to come from an SHFE-accredited warehouse or for at least one additional platform, such as the LME, to enter the market.

Both options face obstacles. With a limited network of SHFE accredited warehouses, commodity flows would steer to Shanghai and a few other ports where the SHFE oversees warehouses. Qingdao, the country’s third largest port, and many other local ports would lose a considerable chunk of the volume they turn over. Any such regulation would therefore almost certainly be met with hostile regional protectionism.

Bringing in the LME, which has a network of 400 warehouses globally and 160 in Asia, would trigger forceful pushback from the SHFE, whose monopoly position would be eroded.

Some hope that repercussions of the Qingdao scandal may be significant enough to force a change of attitude towards the LME and its proven warrant transfer system called LMEsword, including the LME itself.

“The extension of the LME’s warehouse network into mainland China is an important issue for the LME and its users and we alongside HKEx put a high priority on this initiative,” a spokesperson for the exchange comments in light of current developments.

Banks, it appears, would welcome the addition of a trusted alternative player in China for their commodity-based financing, as evidenced by the fact that LME warehouses in South Korea recorded an uptick of 10,000 tonnes of copper immediately after the Qingdao scam came to light, up from just 2,425 tonnes that the warehouses housed at the start of June.

In the meantime, risk management at both local and foreign banks in China will need to be reviewed. Lending on the back of warehouse receipts that only exist in paper form seems more precarious than ever. Perhaps banks will need to go back to the old way of sending inspectors to the ports, comparing actual with claimed stocks. But they’ll have to be smarter than the ones checking De Angelis’ vegetable oil tanks in the 1960s.

.jpg)