In the year 138 BC, a 26-year-old military officer changed the face of Chinese expedition. Born in Shaanxi province during the Han dynasty, Zhang Qian (張騫), a subject of Emperor Wu, was instructed to venture out of the empire and head west.

For years the Han Empire had been the victim of increased attacks by the Xiongnu, a nomadic tribe to the north. As a result, the emperor sought to form a military alliance and commercial ties with entities beyond Xiongnu lands.

Setting out on his westward mission along with 100 men, Zhang endured many challenges throughout the expedition – including 10 years of captivity at the hands of the Xiongnu. After managing to escape, Zhang found himself wandering through the Gobi desert and the Pamir Mountains before reaching Transoxiana – the present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. There he encountered the Da Yueshi people, who graciously received him as an observer of their people and culture, but refused his request for an alliance against the Xiongnu. He returned to his people years later. And while his mission for an armed alliance was unsuccessful, Zhang unwittingly laid the foundation for China’s future collaboration with the peoples of Central Asia, paving the way for the establishment of the ancient Silk Road.

Fast forward to 2017 and China is making another attempt at the Silk Road. President Xi Jinping (习近平), whose father hails from Shaanxi, is reviving trade along the ancient paths. The gravity of the challenge he faces is not too dissimilar from Zhang’s.

.png) Aimed at spurring global growth by deepening Central and South Asia links to China and Europe, China’s Belt and Road initiative has attracted both proponents and critics. Supporters say, connectivity is at the heart of the measure: “Building infrastructure means more relationships between countries,” says Dominique de Villepin, the former prime minister of France.

Aimed at spurring global growth by deepening Central and South Asia links to China and Europe, China’s Belt and Road initiative has attracted both proponents and critics. Supporters say, connectivity is at the heart of the measure: “Building infrastructure means more relationships between countries,” says Dominique de Villepin, the former prime minister of France.But critics see a slowing Chinese economy as the main motivation behind the plan. They note that the plan was meant to redress China’s industrial overcapacity and give its ailing construction industry opportunities overseas. They question its feasibility given that the initiative traverses a swath of frontier and emerging markets beset with political and economic uncertainty.

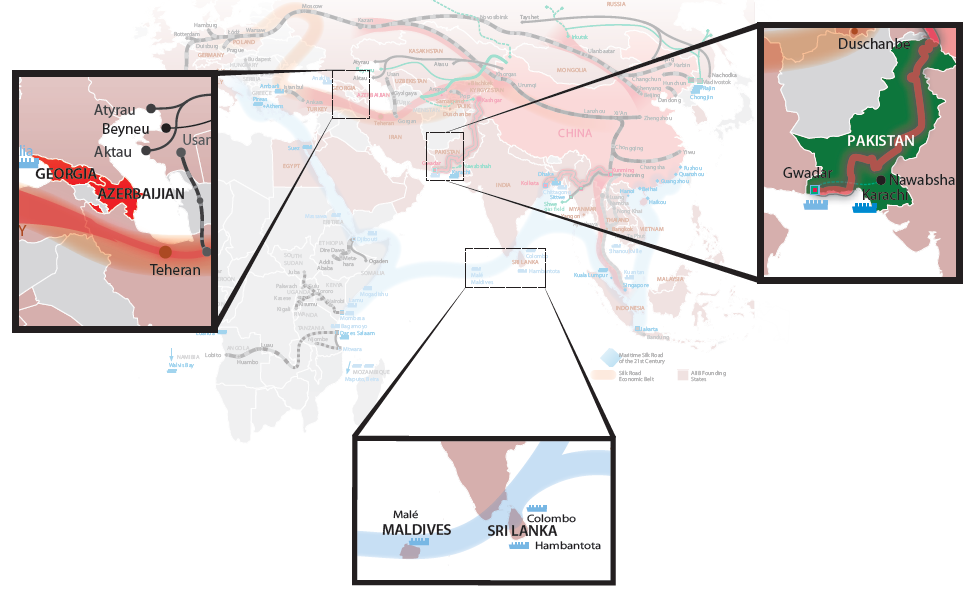

In essence two routes are being pushed. One involves the Silk Road Economic Belt, the land component that aims to facilitate trade and investment in Eurasia. The other is the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route Economic Belt, a route that covers the sea lanes between China and Europe via the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea.

While the spotlight has been on China, just as crucial are the countries that will be impacted by the initiative.

At the recent Asian Development Bank (ADB) annual meeting, finance leaders of Sri Lanka, Maldives, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Pakistan sat down for a conversation with The Asset editors and shared their insights about the Belt and Road plan.

Belt and Road: ‘a necessity’

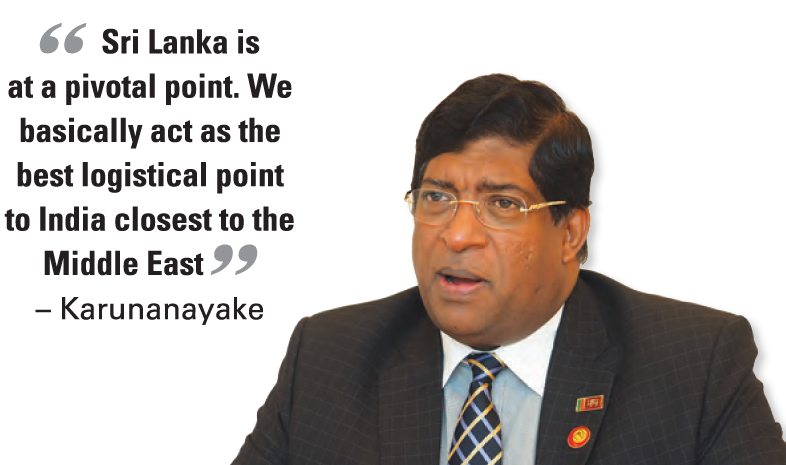

Belt and Road: ‘a necessity’Ravi Karunanayake, Sri Lanka’s finance minister, is convinced his people stand to gain from the Belt and Road scheme. “We find that this area (Belt and Road) has been the shipping route for the last 2,000 years. Maximizing that is certainly a necessity,” he tells The Asset.

Sri Lanka’s major operating ports are located in areas vital to the Belt and Road’s maritime route. In particular, is the Hambantota port situated in the country’s deep south. Last year the government agreed to a 99-year lease of its Hambantota port for US$1.12 billion. Under the arrangement, China Merchants Port Holdings, a Chinese state-owned enterprise, will own 80% of the port while the Sri Lanka Ports Authority keeps the remaining 20%. Hambantota port and the 15,000-acre industrial zone that will be built next to it had been the focal point of public criticisms and fierce demonstrations from landowners, politicians and trade unions. The Sri Lankan government is attempting to blunt opposition to the deal by asking the Chinese company to take on a local company for the project.

“We want to convert debt into equity. We wanted them [China Merchants Port] to tie up with a local government entity,” explains Karunanayake. “It will certainly bring in another US$600 million to US$800 million in investment for equipment and we believe that it will help commercialize the shipping routes that are there.”

Despite the public opposition to the deal, Karunanayake is optimistic the project will benefit the people still reeling from the effects of the civil war. “We want to catch up with lost time and we want to get the fiscal consolidation and showcase Sri Lanka as a shining star,” he states. “It’s a rather realistic approach. This (Belt and Road) has been time-tested over the past 2,500 years. It’s trying to maximize the particular process.”

Karunanayake says the government is open to all forms of investments. “Our foreign policy is ‘friends with all and enemies with none’,” the finance minister shares. “On that basis, we don’t want to take an investment that would offend anybody or reject an investment that would offend anybody. That is the approach.”

Apart from fiscal consolidation on the domestic front, Karunanayake is focusing on increasing revenues. Moreover, he sees the importance of rationalizing expense to ensure sufficient return on cost. He notes that foreign investment, regardless of source, is vital to job creation. “We call upon all our friends to look at Sri Lanka and become part of the nation-building.”

Tourism and development

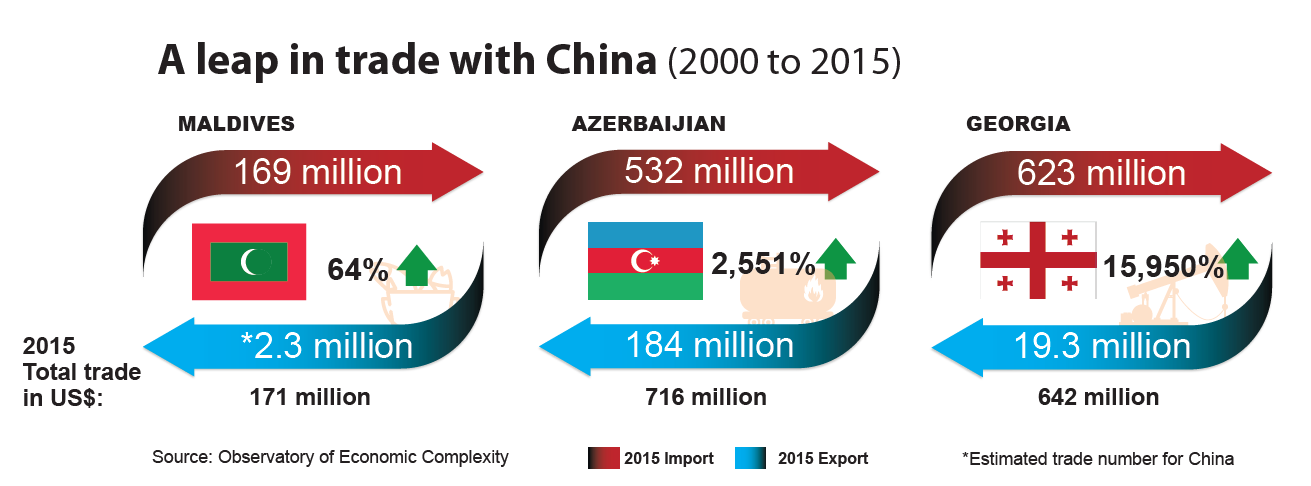

Tourism and developmentLocated an hour away from Sri Lanka is a chain of islands called the Maldives. Representing the smallest nation in Asia, Ahmed Munawar, finance minister to the islands is upbeat about his country’s growing friendship with China. “We have been one of the core founding members of AIIB [Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank]. The Chinese have been very helpful in the redevelopment of our international airport,” he tells The Asset.

In April, Maldives began an US$800 million expansion of its international airport at its capital, Male. The contract to expand the airport was awarded to Beijing Urban Construction Group in 2014 during President Xi’s visit to the country.

“If you look at the numbers we only have one million tourist arrivals annually. With this airport transformation, we are expecting seven times growth,” states Munawar. “This will increase our economic growth because our tourism industry is around 30% of our GDP.” If successful the project would allow Maldives to accommodate even the largest passenger airline, the Airbus A380.

But the infrastructure deal has drawn criticisms from neighbouring India, which has been vocal against Chinese encroachment into its sphere of influence. Two years prior to President Xi’s visit, the Maldives government had cancelled a similar deal valued at US$511 million with India-based GMR Group, leading to a costly legal battle with the Indian firm.

Moreover, China has started construction of the China-Maldives Friendship Bridge, which will link Maldives’ three major islands together. Munawar admits that implementing the projects comes with challenges. “It’s not only the financing cost, but also the administrative costs in mobilizing this kind of scale,” he says.

But it is clear that China’s support is having a positive impact on the nation. “In the future we are hoping to be in the maritime route as well. Despite the Maldives being a small island economy it is an honour for us to be in the Belt and Road. We want to pioneer together with China in order to develop the region as a whole,” he adds. Maldives announced recently its plans to issue its first sovereign bond to fund infrastructure projects.

Transportation and transit

Transportation and transitCritical to the success of the Silk Road Economic Belt is the South Caucasus region. Considered the shortest route from Asia to Europe the region is home to the countries of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, with Russia to the north and Iran and Turkey to the south.

For Azerbaijan finance minister Samir Sharifov, China’s grand plan is a positive development for the country. “We believe that it coincides with the transportation and transit potential development goals of not only Azerbaijan, but also of many countries in Central Asia,” he explains to The Asset.

Since its independence more than 25 years ago, Azerbaijan infrastructure had traditionally been supported by Europe. The export of natural resources such as gas and oil to Europe has played a significant part in the development of the country’s economy.

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, operating since 2006, transports one million barrels of oil a day from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. More recently the country was involved with the US$45 billion Southern Gas Corridor that connects three existing pipelines to shuttle gas from the Caspian Sea to Southern Italy and eventually continental Europe.

Ahead of the Belt and Road scheme, the minister says that the country has beefed up the development of its transport infrastructure. “This One Belt, One Road initiative not only involves transportation routes, but also the development of businesses around this road,” he states. “Therefore Azerbaijan started to implement a big project of constructing a seaport on the Caspian Sea, which will allow Azerbaijan to transship substantial volumes of goods coming from northwest China, Pakistan, Afghanistan and also from Central Asia.”

The port in focus is the Baku International Sea and Trade Port. Located 70km from the Azerbaijani capital, the port is seen as a way of diversifying the country’s revenue sources from oil and gas. Once completed, the port will increase handling capacity to 11 million tonnes of freight and 50,000 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent) per year, boosting trade of other products. The first of three phases will be completed by year-end.

Another key Silk Road infrastructure project for the country is its East to West railway system otherwise known as the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway. Originally scheduled for completion in 2010, the project has been plagued by delays due to the Russia-Georgia conflict and environmental issues. The project is expected to improve the delivery time of goods to 15 days by land compared to up to 60 days by sea. Azerbaijan also plans to develop the North-South transport corridor, which would connect Russia to Iran via Azerbaijan.

“We are very pleased that this initiative [Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway system] might contribute to this One Belt, One Road, which in our view enhances economic cooperation in the Central Asian region,” he says. “We are aware that the governments of Central Asia, in particular Kazakhstan, are also building transport infrastructure on the other side of the Caspian Sea including new port facilities. There is a need for coordination in this activity. We hope that the government of China will contribute in the development of business activities around these new transportation routes.”

Biggest aims

Right across the border of Azerbaijan is Georgia, which like its neighbour has placed much focus on transport infrastructure development. The government has expressed excitement over the Belt and Road plan when it was first announced.

Right across the border of Azerbaijan is Georgia, which like its neighbour has placed much focus on transport infrastructure development. The government has expressed excitement over the Belt and Road plan when it was first announced.

“Georgia was part of the ancient Silk Road and the revitalization of the Silk Road is one of our biggest aims,” explains Dimitri Kumsishvili first deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Georgia to The Asset. “We are heavily investing in our infrastructure to support Georgia’s strength as a transit and hub in the region.”

Apart from its participation in the regional railway link Baku-Tbilisi-Kars system, Georgia is also building a deep-sea port in Anaklia, a region on the coast of the Black Sea. The country last year selected the Georgian and American-backed company, the Anaklia Development Consortium, to start construction on the US$2.5 billion project. The port is scheduled to have its first phase completed by 2020. It will have a handling capacity of 900,000 TEUs, around 50% more than Georgia’s largest seaport Poti.

Once completed, the Anaklia port will allow large panamax and post-panamax ships to dock in Georgian waters for the first time. The port will serve as an import gateway for 17 million inhabitants of landlocked-Caucus and Central Asian countries.

“Georgia is open to the Chinese people and we are open to Chinese investment. We are working now to get additional investment from Shanghai. The commitment we have right now from one company is around US$150 million, but we are very active in the Chinese market,” explains Kumsishvili. China Energy Company Limited recently purchased a 75% stake in Poti Free Industrial Zone to modernize the port’s facilities.

“The business environment [in Georgia] is one of the best in the region,” says Kumsishvili. “We don’t have any restriction on capital repatriation. All together it gives a huge possibility to invest in our country and utilize the potential of what we have,” he says.

Georgia is signatory to major trade deals including the European Union-backed DCFTA (Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area) as well free-trade agreements with the Commonwealth of Independent States and Turkey. In May, China and Georgia signed a trade agreement allowing Georgian goods and services to freely move into China.

For Kumsishvili, the Belt and Road plan poses “no [major] challenges”. Its projects will be built. It’s just a matter of time before Georgia takes part in the overall development, notes Kumshishvili. “There is a huge list of reforms, which we should finalize up until the end of this year,” he adds. “I think we are in the right time and in the right place and as soon as we finalize the construction of this core infrastructure, it will bring a lot of advantages to our country as a transit hub of logistics.”

Regional connectivity

Strategically positioned between the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is China’s long-time ally Pakistan. Pakistan was one of the first countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China in the 1950s and since then the two have developed a close and collaborative relationship.

Strategically positioned between the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is China’s long-time ally Pakistan. Pakistan was one of the first countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China in the 1950s and since then the two have developed a close and collaborative relationship.

Pakistan became one of the pioneers of the Belt and Road after China started building the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in 2015. Estimated to be worth US$54 billion, the infrastructure project involves building a series of roads and railroads that will connect the Western Xinjiang Uygur frontier of China with the Pakistani port of Gwadar giving Chinese goods a direct route to the Indian Ocean.

“The initiative which has been taken by China and Pakistan is going to benefit the entire region,” Pakistan finance minister Mohammad Ishaq Dar tells The Asset. “Regional connectivity is the name of the game for the next millennium.”

The initiative has been met with some pushback from its regional rival India, but the minister believes it is the way forward. “We fully support this initiative despite the reservation of regional countries,” says Dar. “I believe it’s a great initiative and should be taken forward very positively,” he says.

That the China-Pakistan corridor is mutually exclusive to Pakistan and China is, for Dar, a misconception. “The linkage between China and Pakistan is surely there, but the scheme goes beyond to neighbouring countries such as Afghanistan and Central Asian states. It’s a win-win for all. China and Pakistan have a clear resolve to pursue this,” says Dar.

Aside from CPEC, Pakistan has been a strong advocate for regional cooperation and has been involved in CASA-1000, a US$1.16 billion hydroelectric project where Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan will export surplus energy to Pakistan and Afghanistan. The project is expected to be completed in 2018.

Pakistan is also part of TAPI, a US$10 billion pipeline project that will transport natural gas from Turkmenistan to India through Afghanistan and Pakistan. The project recently kicked off in Pakistan and is scheduled for completion in 2018.

“In the next 20 years if you really want to accelerate growth further, increase the living standard of the people and reduce the poverty in this region. I think we need to focus on infrastructure development, economic financial integration as well as the regional connectivity,” states Dar.

Absorptive capacity

Seeking to boost momentum for the Belt and Road plan, China held its Silk Road Forum in Beijing in May bringing together leaders from various countries including Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indonesian President Joko Widodo. During the forum, China pledged US$124 billion in Belt and Road projects and President Xi called for peace by promoting inclusiveness and free trade.

Seeking to boost momentum for the Belt and Road plan, China held its Silk Road Forum in Beijing in May bringing together leaders from various countries including Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indonesian President Joko Widodo. During the forum, China pledged US$124 billion in Belt and Road projects and President Xi called for peace by promoting inclusiveness and free trade.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and the International Monetary Fund have jointly committed to increasing funding for the Belt and Road projects. Moreover, the PBoC signed a memorandum of understanding with the Czech National Bank with respect to information sharing. They committed 100 billion yuan (US$14.5 billion) in additional capital for the Silk Road Fund.

From the shores of the Black Sea to the Gobi Desert, infrastructure development is in full swing along the historic Silk Road. The focus has been mostly on China and its motivations behind a hugely ambitious infrastructure plan. As the projects are being rolled out, it is becoming clear that the Belt and Road’s success also lies on the motivations and readiness of the host countries to fully utilize and benefit from the development.

Many of these countries are facing some of the toughest economic conditions. To succeed in the initiative, they will need to overcome a host of political challenges as well as operational and security barriers. The overriding concern is their governance structure and the ability of their public institutions to handle massive inflows of funds. Amid unstable governments, issues of corruption and volatile politics, these projects faced considerable hurdles.

The road to success depends as much on the countries willingness to embrace progress as on China’s determination to make it work. Belt and Road plays to China’s strengths. It is cash rich and highly experienced – infrastructure development has modernized China in less than two decades. More than its acumen in building projects, the Belt and Road will put to the test China’s foreign relations prowess and regional leadership. Many of the moving parts across the 67 countries that the initiative traverses are beyond its control.

The ancient Silk Road came to an end in the 14th century as nations along the Silk Road began unwinding economic and cultural ties following the demise of the Mongol Empire. With its vision for the Belt and Road, China is determined that history doesn’t repeat itself.

.jpg)

.jpg)