The carbon emission and net zero targets that have committed countries to combat climate change continue to be a key topic globally. In Asia, Korea aims to get a net zero emissions target by 2050 into legislation, while China is committed to incorporate this into its policy documents in order to achieve net zero emissions by 2060.

As the shift towards a low-emission, decarbonized world accelerates, countries and territories across Asia are looking to the November COP26 Summit to finalize direction on a future system for pricing carbon.

At present, environmental, social and governance (ESG) screening uses qualitative factors, such as governance or reputational issues, to assess corporates’ actions in this domain. However, these measures are not necessarily forward-looking and are often difficult to compare, even within single industries. As a result, they fail to provide an accurate assessment of future environmental risks. Moreover, if the world is to have a realistic chance of limiting global warming and achieving net zero by 2050, disclosure alone is insufficient.

Current ESG standards provide a bridging solution while the world waits for the major economies to decide on a formal direction. Until disclosures are made mandatory and standardized to the point where they can be included in financial statements, and a “hard” price is put on carbon, investors will have to rely on these “soft measures”.

Delivering greater emissions cuts

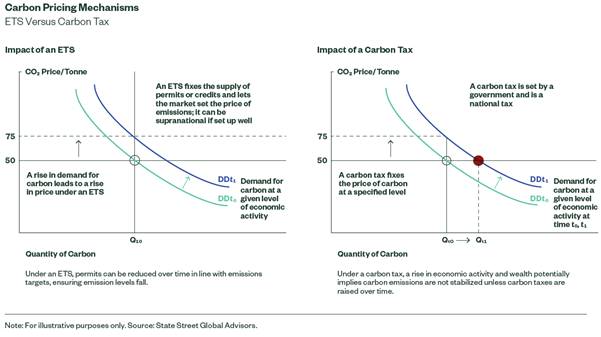

There is no internationally agreed carbon pricing standard, and the fragmented nature of national and regional pricing mechanisms creates more complexity for investors. According to the International Monetary Fund, many governments now see carbon pricing – either through an emissions trading system (ETS) or via a carbon tax – as essential for transitioning to decarbonized economies and achieving emissions reductions.

Of these potential solutions, the case for a supranational ETS or carbon market is growing stronger.

An ETS can deliver significantly more in the way of emissions reductions than a carbon tax. Using new technologies to track and determine the cost of emissions, an adequately constructed supranational ETS or carbon market would lead to a continuous rise in the carbon price. This, in turn, would trigger a rapid real economic response in terms of innovation and energy efficiency, leading to lower emissions.

In contrast, we believe a carbon tax would be less efficient. Carbon taxes that need to be imposed nationally, could meet with resistance from local populations and would not necessarily lead to a converged global carbon price. Assessing the actual cost of carbon would, therefore, remain problematic.

Most importantly, under a carbon-tax system, a rise in economic activity and wealth potentially implies an increase in carbon emissions, which cannot be stabilized unless carbon taxes are continually raised.

There are drawbacks to an ETS system. It can be more complex to understand than a straightforward tax and, therefore, a harder sell to politicians. It also requires sophisticated monitoring and supervision. Before the system can be introduced, a broad-based agreement on price and emissions caps would be necessary. On balance, however, an ETS will better serve the cause of steadily reducing global emissions.

Carbon pricing – a new landscape of winners and losers

A carbon price would radically change both the competitive landscape for industries and the environment for equities.

Equity markets have already been pricing the impact of carbon costs in sectors such as energy and utilities. Both sectors have demonstrably underperformed, and their representation in global equity indices has steadily decreased. However, emissions in other sectors are more difficult to quantify. Within industries, some companies are ahead of their competitors in terms of measuring emissions, and in many cases, necessary measurements of supply-chain emissions are not factored in.

Carbon pricing will crystallize the costs of emissions on competitiveness and pricing power, in turn affecting top-lines and margins. In some industries, physical risks to assets from climate change will also have to be considered, alongside obsolescence and stranded costs.

Pricing carbon will, thus, generate a new landscape of winners and losers. A company with the lowest emissions today, and hence the lowest transition costs, will win tomorrow because it will require less investment to meet emissions targets when carbon is priced. Investors will also seek opportunities or investment partners to identify companies that are ready or potentially able to contribute to the transition to net zero.

The political will for change is gathering pace

The COP26 Summit will take place in an environment where the political will to act on climate has never been so strong. The US administration is taking climate action seriously, and a well-constructed market-based ETS is likely to be more acceptable to the US Senate than a carbon tax. Several governments have set concrete deadlines to reach net-zero emissions. France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, New Zealand, Switzerland, South Korea and Canada have committed to 2050, Sweden to 2045 and China to 2060.

Adding to the sense of urgency are the major central banks, which see climate change as a real threat to future financial and economic stability.

Asian economies now await decisive action. The COP26 Summit in November should confirm whether hard metrics will be introduced, alongside level and potential guarantees for an annual minimum carbon price. (See “Proposal for an International Carbon Price Floor among Large Emitters”, IMF Staff Climate Notes, June2021, which is currently before the IMF Board.)

If no decision is taken at COP26, then soft measures will likely endure, despite their complexity, incompleteness and ineffectiveness. This would risk squandering the opportunity presented by a growing global political consensus.

However, a supranational ETS or carbon market that forces emissions to be quantified, standardized and formally disclosed in financial statements will, over the next decade, have a material impact on all financial investments and, we believe, help bring about a significant reduction in global emissions.

Michael Solecki is chief investment officer of fundamental growth and core equity team at State Street Global Advisors.