Value investing is the most tried and tested investing strategy, having been shown to be robust in virtually all asset classes and geographies over the long term. Yet today we are in the midst of value investing’s worst run ever, and there are legitimate reasons why this should be beyond the simple explanation of “value stocks are not popular these days.”

Over the past decade, growth stocks (stocks with high growth rates of revenue and earnings, regardless of valuation) have beaten value stocks (stocks selling cheaply relative to its revenue, earnings, and book value) in virtually all markets. In the US, growth has outperformed value by about 3 percent per year. Globally, the outperformance is about 2 percent per year, while in Asia ex-Japan it has been about 1.5 percent per year.

The primary reason behind this phenonemon is that the global economy is undergoing a transformation from an asset-heavy economy to an asset-light one. Historically, companies needed to invest heavily in assets such as factories, inventories and machinery equipment to produce revenue and earnings growth. Now however, many companies find that they don’t need that much capital to grow.

Consider the two largest Chinese companies by market capitalization: Tencent and Alibaba. Just ten years ago, they were nowhere near the top two spots. Back then those positions belonged to state-owned Petrochina and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC).

Since 2009, Petrochina has cumulatively spent approximately 2.65 trillion yuan (US$380 billion) on capital expenses to produce a revenue growth rate of 6% per year. ICBC has spent 265 billion yuan to produce a revenue growth rate of 10% per year.

Compare that to Tencent, which only spent 145 billion yuan to produce a revenue growth rate of 43% per year. Or Alibaba, which spent a mere 85 billion yuan for a revenue growth rate of 72% per year. (For context, in the past decade, PetroChina’s stock price has declined 50% while Tencent’s has increased 40,093%).

Software tech companies like Tencent and Alibaba don’t sell tangible products that require factories and machineries to produce them. All they need is some software that appeal to the masses and the internet to distribute that software to customers at extremely low costs (i.e. it doesn’t cost them anything to copy and sell its software to one additional customer).

In addition, software tech companies enjoy network effects that make their software more valuable to the more people use them: the more people who use Alibaba for e-commerce or Tencent for social media, the more valuable these platforms become to suppliers, advertisers and consumers. This creates the tendency for everyone to standardize on a single platform, often characterized by a “winner takes all” dynamic. In aggregate, these effects generate huge growth rates and market shares at very low costs.

In this kind of environment, it makes sense that traditional value investing has suffered. Not only did it fail to anticipate the enormous growth rates that these new breed of tech companies have generated, but it has also mistakenly focused on assets as its yardstick of value.

In virtually all value indices, such as the Russell 3000 value index and the MSCI value indices, a low price-to-book ratio is the primary metric for categorizing a stock as a value stock. The ratio compares a company’s market capitalization against its book value (which is its assets minus liabilities).

Back in the old days, this was a reasonable thing to do. As companies needed assets and liabilities to produce revenue and earnings, it was sound logic to think that book value is a good measure of a company’s intrinsic value. In today’s world, thinking this way without considering tech’s inherent advantages would be folly.

It isn’t just our focus on book value that is the problem, its also the the way in which we measure it. Due to old financial report standards, advertising and research and development (R&D) costs are mostly expensed immediately rather capitalized on the balance sheet. This has led to book values being underreported, which in turn makes the price-to-book value appear artificially high.

For instance, think of the tremendous value advertising and R&D costs have generated for Alibaba and Tencent. The two companies have together spent close to 200 billion yuan on advertising and R&D since their founding. These activities have helped Alibaba and Tencent become household names in China and the rest of the world, but instead of creating an asset like PetroChina’s investment in factories and equipment, they are mostly deducted immediately from revenue as operating expenses.

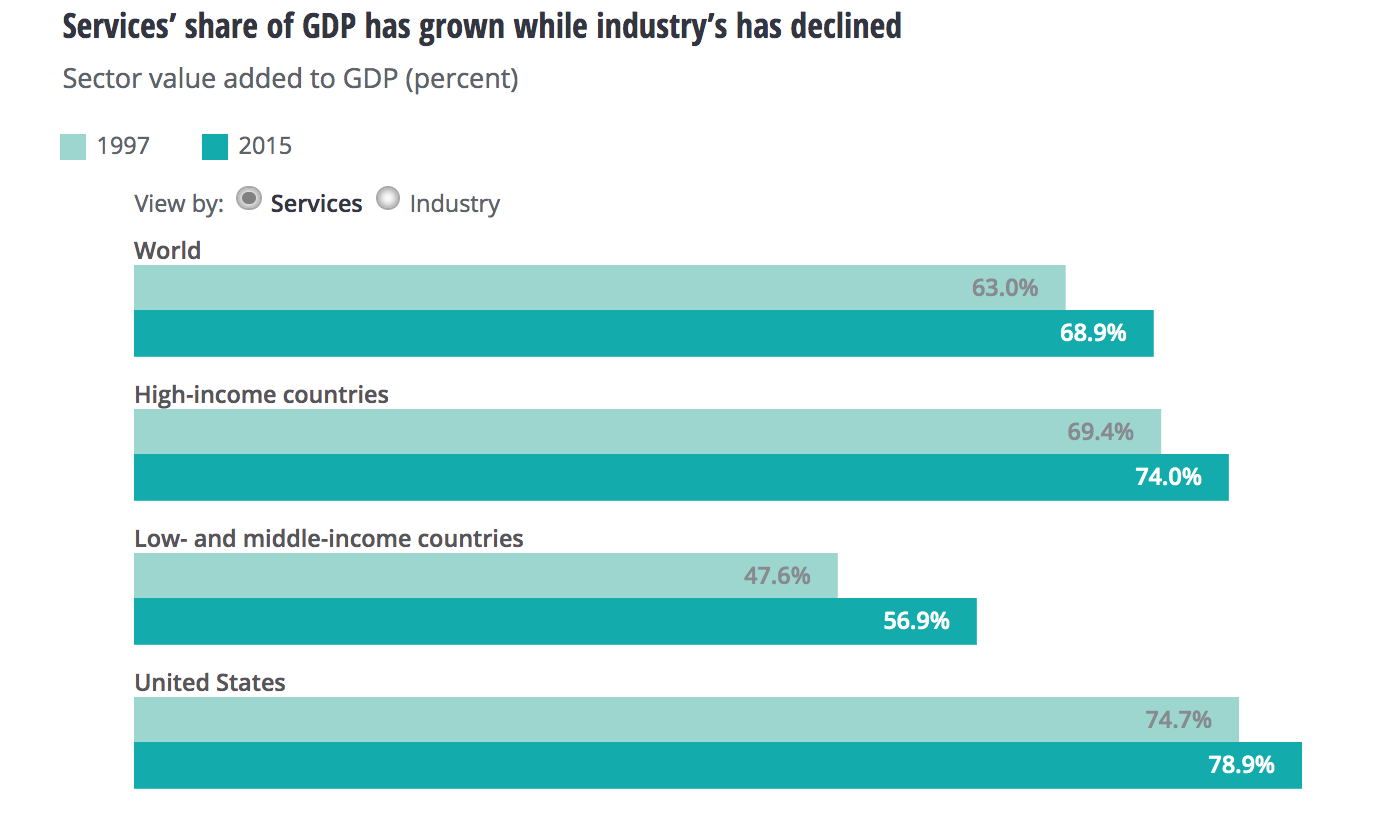

As the global economy carries on with its transformation from a manufacturing, industrial economy to a service-based one, it appears quantitative value metrics will continue to suffer. In the US, the service sector grew from approximately 40% of GDP in the 1945 to roughly 80% today. For high-income countries, the service sector accounts for about 75% of GDP. In low-income countries, it's about 60%. In China, it’s about 50%.

However, although quantiative value metrics like price-to-book have lost much of their efficacy, there are value investors who have learned to adapt and change with the times. The most famous value investor of them all, Warren Buffett, is a prime example.

Buffett started his investment career buying quantitatively cheap stocks (“cigar butts”, he calls them, as they only have a few puffs of value left). But starting in the 1950s, he recognized the economy was becoming less dominated by industrials, while consumer companies such as Procter & Gamble, Sears Roebuck, and General Foods were on the rise.

With the help of his partner Charles Munger, Buffett recognized the primary driver of business value for this new breed of companies was not the hard assets of the industrial generation. Rather, the value lay in the company’s brands.

Buffett said in 1967, “Although I consider myself to be primarily in the quantiative school, the really sensational ideas I have had over the years have been heavily weighted toward the qualitative side, where I have had a high-probability insight. This is what causes the cash register to really sing.”

Recently, Buffet’s evolution has gone even further with investments in tech giants Apple and Amazon, two so-called growth tech stocks that traditional value investors wouldn’t dare go near.

Clearly, there is then a way for value investing to survive. The investing discipline just has to evolve with the times and recognize that growth should be included in the calculus, not ignored altogether. Buffett himself noted that value and growth are “joined at the hip”.