“The wise make their own decision; the ignorant follow the crowd”

Chinese proverb

Back in the late 1980s, in the latter stages of the Cold War, an urban myth began circulating about then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, his Chinese counterpart Deng Xiaoping, and US President George H.W. Bush. In the story, Gorbachev’s chauffeur-driven car comes to a junction and pauses. Pointing left is a sign labelled “Socialism”, pointing right is a sign labelled “Capitalism”.

Irritated by his driver’s indecision, Gorbachev barks: “Why the delay? To the left!”

A short time later, Bush Snr’s car sweeps through the junction, taking the righthand fork at high speed. Bush gestures his approval to his driver – they are on the right route.

As evening draws in, Deng’s car arrives at the same junction, and the driver is told to stop for Deng to get out of the car. After assessing both directions for a while, he nods to himself. He then reverses the sign and returns to the car. “To the right – to socialism!” Deng instructs his driver. “And don’t look back!”

Fast forward to today, and China, under the strongman leadership of Xi Jinping, is again at a fork in the road as it seeks to achieve its long-term goals of sustainable prosperity and stability. Based on recent events, policymakers seem prepared to take potentially significant pain to remap China’s growth model.

Multiple factors have precipitated this shift, not least the country’s ageing population who face the risk of “getting old before getting rich”, coupled with a more confrontational external environment.

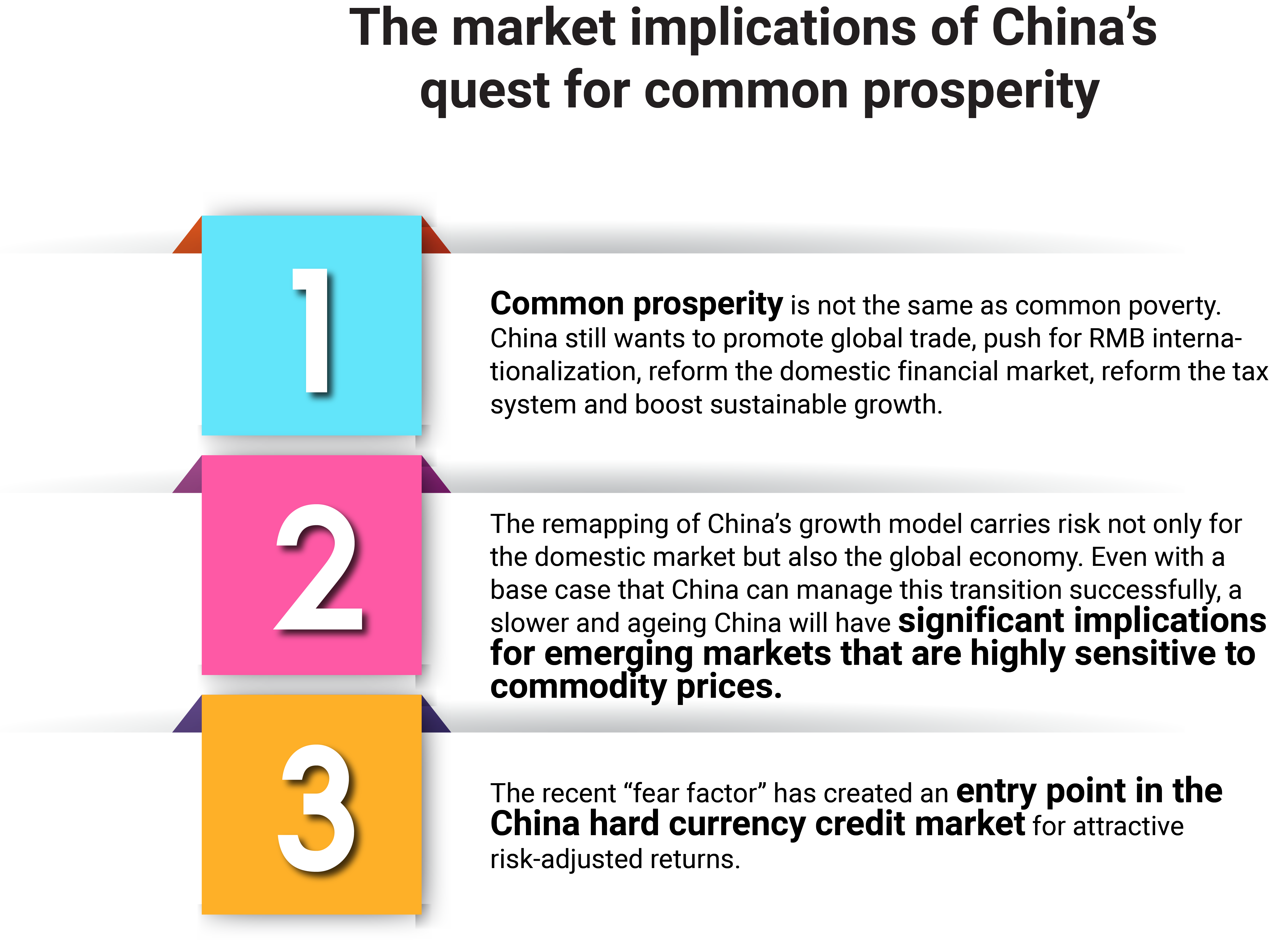

A slew of new regulations in the Year of the Ox, including a tightening of rules for China’s booming tech sector, have spooked domestic and international markets. While some changes may seem to have come out of nowhere, many have been well signposted under the aspirational goal of “common prosperity”. Notwithstanding the clear economic imperative for these changes, if we consider them in the context of the last 100 years in China, we can better understand their rationale and how they relate to Beijing’s vision for the future.

If China can successfully remap the contours to its growth model without triggering a hard landing or global recession, it should present attractive opportunities for investors. This remapping also raises important questions for economies elsewhere, not least whether there will be a demand shock to commodities that will disproportionately hit raw material-exporting emerging markets.

A century of Chinese communism and the germination of targeted intervention

After tremendous growth in the last 30 years, China is big enough and confident enough to determine its own way forward. Not for the sake of being different, but because it has taken its own idiosyncratic path to this point and has its own singular influence on the way it approaches national and global challenges. When governing 1.3 billion people, at the human level there will certainly be pressure from “events”, casualties along the way, and no doubt costly mistakes.

We should not lose sight of the fact that the Chinese economy is fundamentally a planned economy. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a point for reflection on what has been achieved and what still needs to be done before the next centenary of great importance, 2049, which will mark 100 years of the People’s Republic of China.

But we should also remember other events that took place in the run-up to China’s adoption of communism, events still seared in the national psyche.

In the mid-19th century, a weakened China was forced into granting concessions to foreign powers and to open ports for trade in a series of unequal treaties. The reasons for the Qing Dynasty’s inability to protect China are manifold, but one important aspect was its belief that China was the Central Kingdom. It focused internally, while the rest of the world progressed in the white heat of technological change that characterized the industrial revolution.

This inward-looking philosophy hampered Chinese progress, in stark contrast to the “new” leaders in the rest of the world. This is a mistake modern China is keen not to repeat; it wants to be a global trading partner but on its own terms.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Eight-Nation Alliance (Germany, Japan, Russia, Britain, France, the United States, Italy and Austria-Hungary) marched into a China in disarray. There was much looting of China’s cultural relics and its heritage. The shame of these events hung heavy on the shoulders of many Chinese and was, in part, a catalyst for the formation of the CCP in 1921 – both a political party and revolutionary movement.

The party’s founding fathers made a number of pledges, including for xiao kang zhi jia (小康之家), which translates as “common prosperity”. This ideal resonates with the party under Xi – it was deemed a “fundamental principle” of Chinese socialism at the 18th party congress in 2012, while the latest five-year plan for 2021-2025 demanded an “action plan” to achieve clear progress towards realizing this objective fully by 2050.

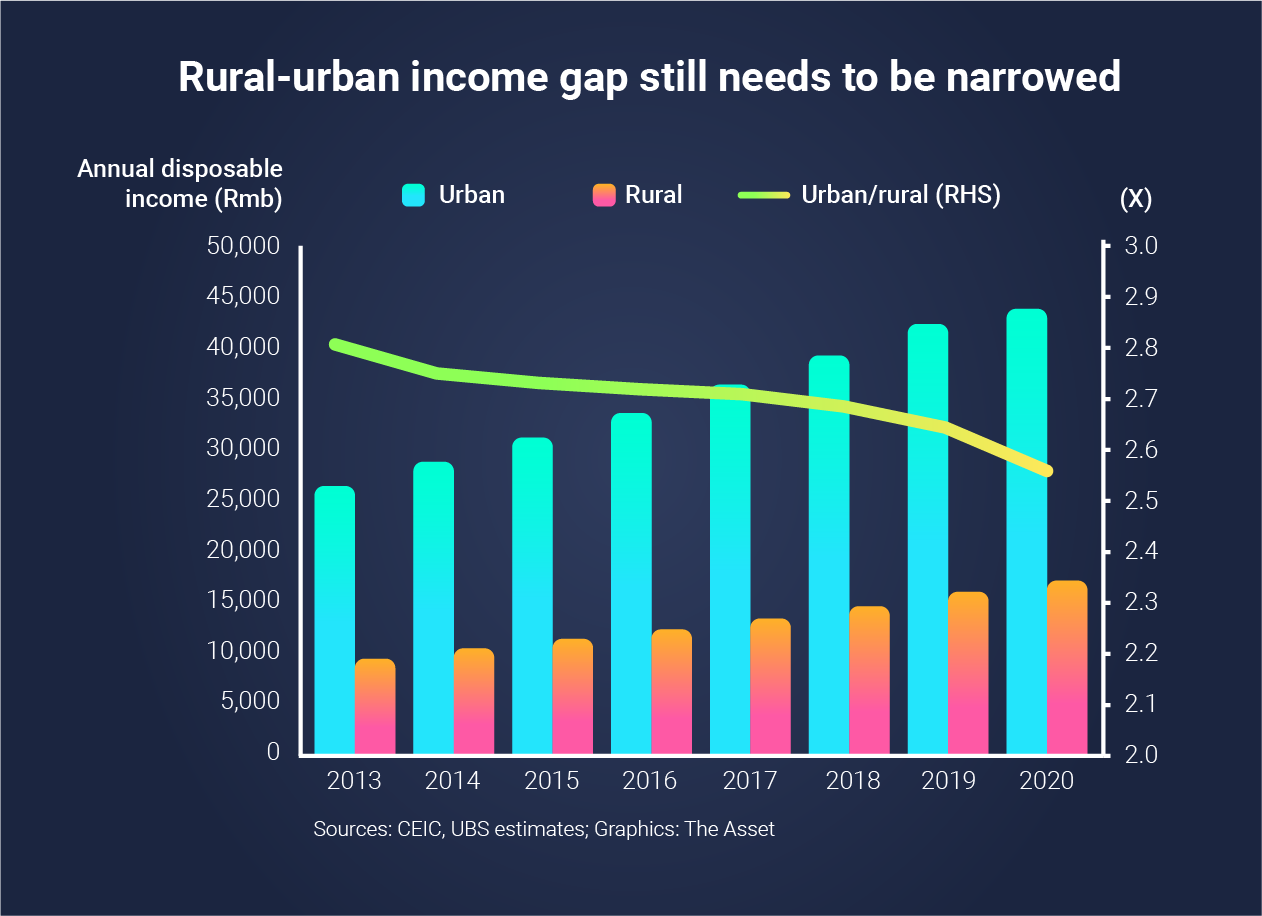

Common prosperity is defined as “a more equal society with better social welfare, not egalitarianism, and entails further household income growth, better public services, stronger social safety net, narrower income gap between different groups, regions and rural-urban areas.”1 Progress towards narrowing the urban-rural income gap has been steady over the last eight years,2 as illustrated below. The greatest factor in China’s wealth inequality is home ownership – with estimates of it accounting for up to 80% of the difference. The Chinese government understands it needs to address this issue if it is to secure long-term stability.

This narrowing has happened as overall poverty in China is being eradicated. The story is optimistic – the baseline standard of living is rising as the gap between urban and rural incomes is being closed.

Even after the formation of the CCP, China’s “century of humiliation” continued with the civil war between nationalists and communists put on hold to present a “united front” against a full-scale invasion from Japan in 1937.

History belongs to the victors, and modern Chinese history reports that the country was liberated by Mao Zedong and the CCP in 1949 and has been building a more secure and prosperous future of its own since then. The Chinese people have looked to distance themselves from the pain and humiliation of foreign direct rule/invasion and re-establish the country as a respected force on the world stage. Furthermore, the modern Chinese state was forged, in living memory, through revolution – so there exists a not unfounded fear of re-revolution. Through long-term planning for prosperity of the many, the CCP is mitigating against instability and this ever-present threat.

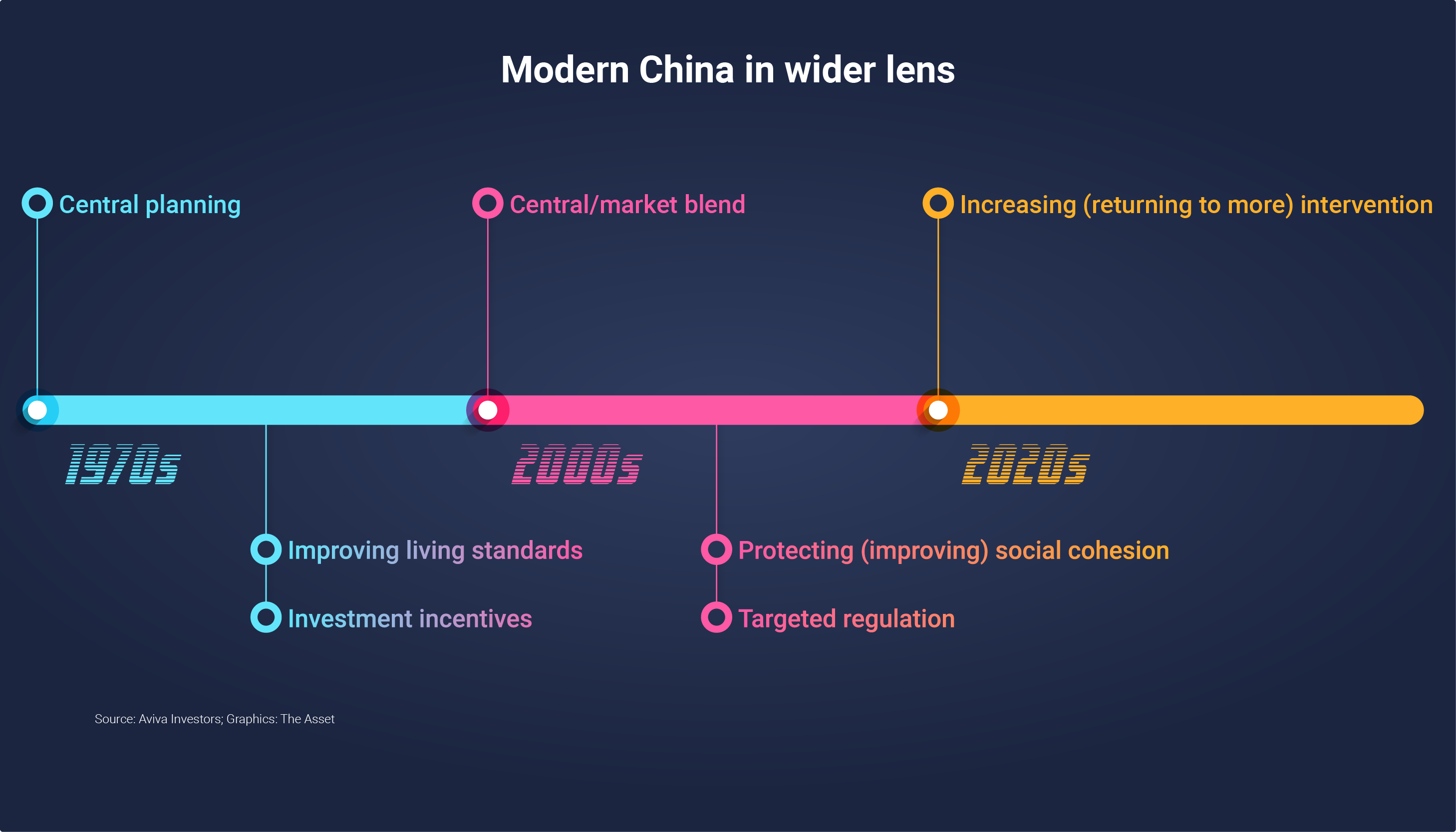

More recently, investors have begun to worry about sweeping regulatory changes in key sectors. But we need to remember China’s journey to and beyond that signpost, what it has endured along the way and look at these changes through a wide-angle lens. If not overtly predictable, these changes are rational, and investors should continue to seek opportunities that a well-run, albeit fundamentally planned, economy can create. The timeline below looks at the balancing tensions that China has been managing over the last 50 years and provides context to recent regulatory shifts and the opportunities they may lead to.

With this simple model as an historical backdrop to better understand the rationale for recent regulatory changes, it is worth exploring other events where China’s recent history has had an understandable influence.

Firstly, the country’s rapid rate of growth in recent decades cannot go on forever – not least because the baseline has risen and the population is ageing. There will be a flattening of the growth curve – although to a still more than respectable level for most large economies. Nevertheless, China’s economy will change to deliver a better “quality” of growth.

Allied to this, and to fulfil the “common prosperity” pledge, the standard of living for many low-income households must improve. This explains a renewed focus on sectors like healthcare and education with a simultaneous cooling of the property sector. The impetus behind such thinking is highlighted by the increased frequency of Xi referencing “common prosperity”, as shown below3.

‘Common prosperity’ is not new

.png)

The slogan: “A house is for living in, not for speculation”

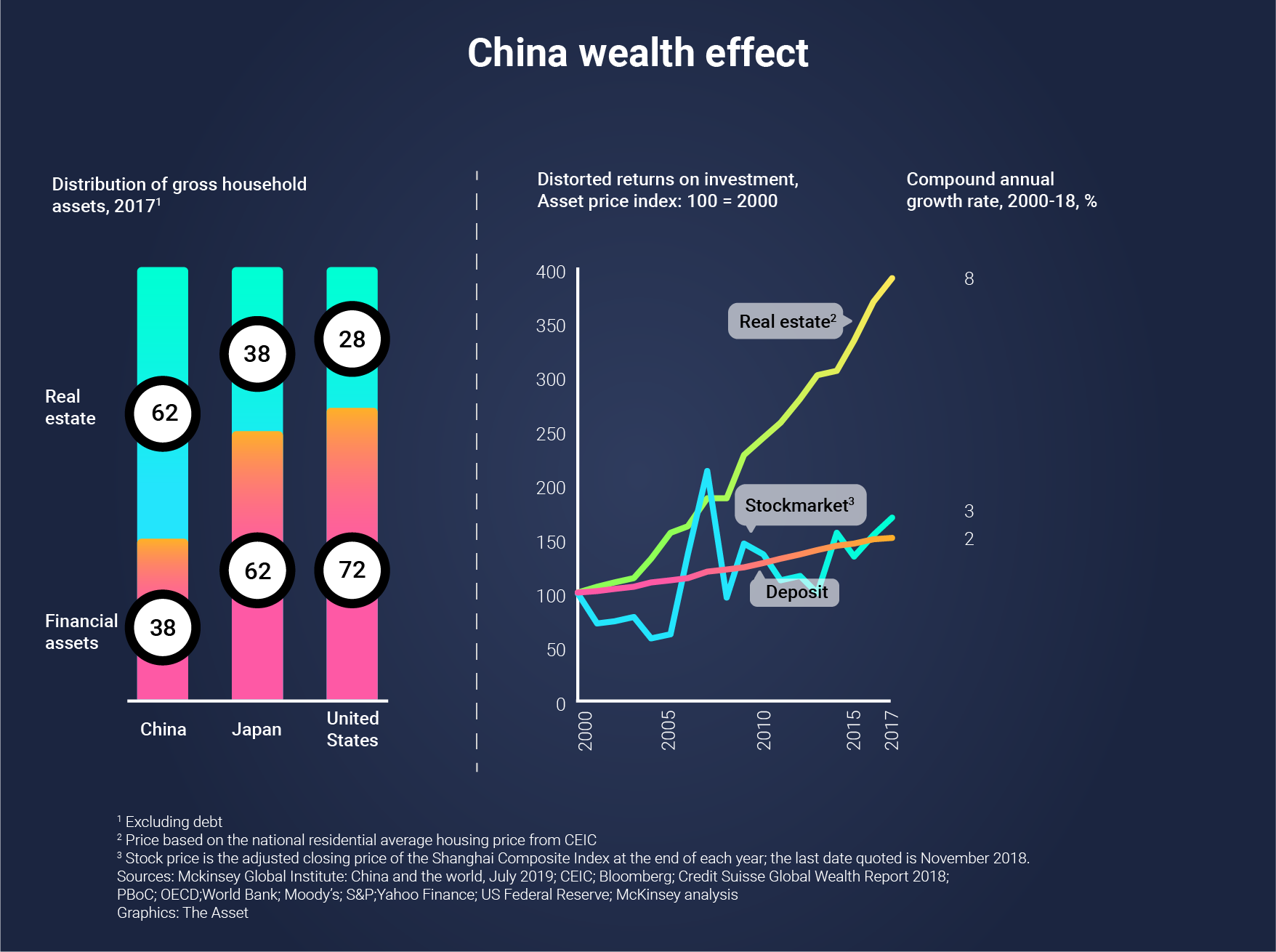

Rising house prices can and do redistribute wealth within an economy – increasing the wealth of the “haves”, homeowners, but effectively reducing that of the “have nots”, those yet to own a house. The property sector, while fundamental in raising people’s living conditions, should be seen as part of the get-rich-first attitude, which has been encouraged to propel China down the road of economic development. Although extremely important – and housing must be both affordable and accessible –property is not a strategic sector as it will not deliver “quality” growth.

China has recently hit the headlines, and raised investor heckles, through two major credit events – involving property developer Evergrande and distressed debt asset manager Huarong – in addition to the introduction of new regulations. It is important to understand the linkage between these events.

China experienced breathtaking growth, fuelled by rapid industrialization, after joining the World Trade Organization. This growth was prompted by China’s “flirtation” with western capitalism. Evergrande and Huarong are classic symptoms of agency theory, where the management of these companies embarked on aggressive debt-funded growth at the expense of the interests of other stakeholders, including shareholders. A critical difference between the two is that Huarong is 61% owned by the Ministry of Finance, making it difficult for Beijing to distance itself from its debt, whereas Evergrande is a private conglomerate.

Huarong looks to have been bailed out by the government to prevent embarrassment and avoid what commentators predict could be China’s “Lehman moment”. Evergrande, on the other hand, has been left to meet its fate as market forces direct.

Evergrande is the story of a private, street-smart operator. The company was opportunistic and aggressive on the way up, and grew rapidly through debt. This model worked for a while – but Evergrande failed to see the tide turning in time – despite this being well signalled by the government. Evergrande was collateral damage, its business model an obstacle in the way of what China is seeking to achieve in redistributing wealth and focusing on more strategic sectors.

Despite the reaction of investors to the Evergrande and Huarong credit events, the government’s handling of them was predictable. Prior to 2018, the government was trying to rein in leverage, especially in the real estate and local government sectors, but this was interrupted by escalating trade tensions with the United States and then Covid-19.

The government’s hardening attitude to real estate was always going to be a bold move as construction and its supply chain account for 25% of the Chinese economy – half of the world’s cranes are in China – and up to 40% of local government fiscal revenue4. But policymakers are keen to deleverage a sector that has experienced bubbles that affect lives and livelihoods. As the chart below demonstrates, wealth is being built in the real estate sector and this, set against the articulated strategic thrust of the government, is creating and exacerbating inequality.

The state’s growing influence in tech

China aspires to be a technology-driven country. The pace and depth of the uptake of technology and innovation is colossal. During one of our annual trips to China in 2016, my European husband took our young daughters to paint pictures at a market stall in the southern city of Guilin, while I was away meeting local issuers. My daughters (and husband) would sit on tiny plastic stools around tiny plastic tables arranged in such a way as to be as far as possible away from the moped rat runs – a scene that would be replicated across towns and cities in China at the time.

As he had done on many occasions in previous years, my husband ordered three ice lollies in broken Mandarin from the adjacent street stall and held out a 10-yuan note. To his surprise, his money was refused; the street vendor would prefer to turn down the sale than to take cash. He told my husband, “No WeChat, no deal.” This was a clear illustration that the winds of technological change are perhaps stronger and more far-reaching with early adopters in countries looking to “catch up” compared to those with legacy systems and perhaps populations mostly made up of late adopters.

Tech is a sector of great strategic importance and commands the focus of Chinese policymakers. Tech regulation is not unique to China, and there are a myriad of motivations driving this, including anti-trust and the desire to nationalize big data5.

As things currently stand, big data is the sole property of a few large platforms – for China to move up the value chain, it is desperate to digitalize the economy and believes big data should be a national resource and open to everyone. This is a clear ideological fracture with the way many other governments view data, personal privacy and competitive advantage.

The recent introduction of regulations for the tech sector has perhaps been implemented without enough thought on the wider repercussions – although it is unlikely the government’s motivation is to attack the private sector nor close its doors. History has hopefully taught China that a closed-door approach is risky, perhaps allowing its rivals to again surge ahead.

A contemporary example of China’s learning from history, being open to outside ideas, and having a willingness to learn from others in order to catch up is its reaction to US trade tensions. From March 2018, the restrictions imposed by the US on high-tech goods made policymakers sit up and take notice. If China really wants to be a powerful and well-diversified economy, it must redirect resources and soon. Time is of the essence in the face of a less extreme, yet more difficult to handle, US administration6. Too much of the economy is currently focused on construction and infrastructure at the expense of adequately resourcing high-tech and more strategic sectors.

Education for all?

Another example in the drive for “common prosperity” that aligns with the founding ideas of the CCP is the education sector. For centuries, the education system has been based solely on meritocracy; a public service central to the implementation of creating and maintaining a fair and inclusive society.

In the context of education being a force for public good, it could be perceived that any for-profit provision is not wholly desirable. It is extremely important for the children of Chinese families to get into good schools – and as the exam system is “clean”, the only way to progress is to study hard. This is where private and public equity-funded organizations stepped in to exploit this need and, in the process, create a profitable after-school tutoring sector.

Unfortunately, the increasing price of after-school tutoring opportunities to get into the best schools became unattainable for those outside the affluent middle class, which did not fit well with the vision of China for 2049.

There was a double whammy when it comes to demographics. China is rapidly approaching an “ageing population” – the country’s working population peaked in 2012 – and needs many more higher-value workers (better educated and prepared for the challenges of the 21st century) entering the economy. The current birth rate in China is approaching zero, which carries huge risks for economic growth, a situation that has recently been exacerbated by the increased financial burden of raising a family and rising housing costs.

This obstacle must be removed or at least reduced to allow better conditions for economic (and family) growth. A second large part of this burden, after the cost of housing, is the perceived need for expensive after-school tutoring for the child to be a “success”.

To fulfil its pledge to create “common prosperity”, to fit with its desire for “quality” growth, and to fit with the culture of a long-term planned economy (perhaps at the expense of market sentiment), the government felt the need to act aggressively and decisively, with strict and comprehensive regulations to make the after-school tutoring sector not-for-profit.

This has had a significant impact on the education sector but also sent shockwaves through other sectors and spooked international investors, although these actions must also be viewed as rational in the context of China’s history and the issues it faces today and tomorrow in its search for equality, sustainable growth, social cohesion and fundamentally the stability of the CCP.

Navigating the next fork in the road

As a result of the global pandemic, questions have been raised about the role of governments in an economy, and we have seen an expansion of their influence – especially in developed economies.

China has staged a GDP per capita growth miracle, which has risen from US$500 to US$10,0007 in 25 years. While this has led to improving living standards, it masks important details. During this period, it has been necessary to create an environment where some have become super rich to catalyze economic growth. Relative to developed markets, China still lacks a sophisticated tax system and social security safety net, which explains why the government is not satisfied with the progress it has made in lifting its poorest citizens out of poverty.

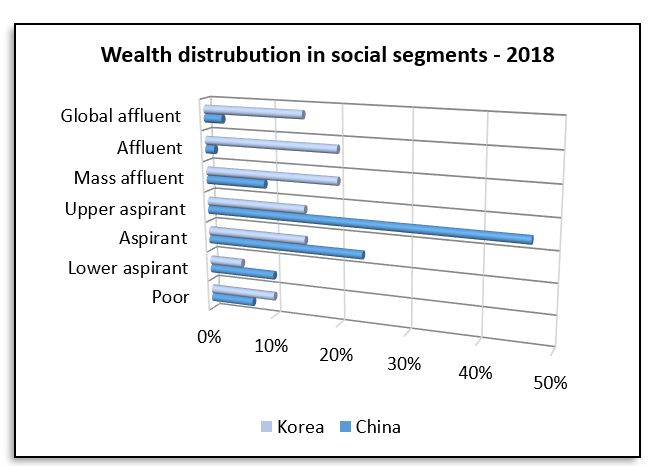

To deliver on the goal of “common prosperity”, China wants to further reduce the “fat tails” in GDP per capita. The chart below for 2018 shows how China has its desired bulge in the middle compared to its near regional neighbour South Korea (albeit on a different path)8, but believes there is work to be done to better distribute wealth in line with the pledges made by the CCP a century ago. In some respects, this is what continues to drive modern-day China.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute, China and the world, July 2019

While there should be no doubt that China’s recent policy changes have been motivated by political goals, there is also an economic rationale in the efforts to channel resource where it is needed for the common good. It is an ambitious programme that would doubtless only find fertile ground in a state where the ruling cadres are secure for years to come, with limited to no independent institutions and perhaps what one might describe as a communal culture. This is a different game to the one most international investors are used to playing.

The emphasis on common prosperity and further equality is what will drive a rebalancing of the economy. This will have a flattening effect, but should deliver more sustainable economic growth as well as social cohesion, which makes sense for China at this point in its journey.

China has travelled a long way in the last 100 years and perhaps it doesn’t really matter what it says on the signpost. It will remain a planned economy that will look for opportunities for international collaboration with its own twist. For investors, there will continue to be attractive opportunities for those who understand where China has come from, recognize why it is on its current path, and heed its signals.

Amy Kam is a senior portfolio manager at Aviva Investors. Based in London, she co-runs Aviva Investors’ emerging markets corporate bond strategy.

*****

1Common Prosperity and Policy Implications - UBS

2 Common Prosperity and Policy Implications - UBS

3 Bloomberg

4 Ting Lu, Nomura China Economist

5 Thanks to Becky Liu of Standard Chartered Bank for valuable insight during our conversations.

6 Thanks to Ning Zhang of UBS for many extremely helpful discussions on China growth and US-China confrontation.

7 World Bank data.

8 McKinsey – China and the World: inside the dynamics of a changing relationship, July 2019.